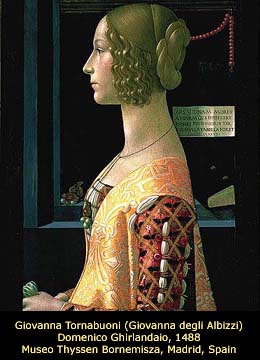

Giovanna Tornabuoni

(née Giovanna degli Albizzi )

Domenico Ghirlandaio (Domenico

di Tommaso Bigordi), 1488

Renaissance

Museo

Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid, Spain,

Portrait of Giovanna Tornabuoni is one of most

emblematic picture of Domenico Ghirlandaio. Domenico Ghirlandaio (1449 -

1494) was one of the widely recognized painter in his period. His name

was delivered from his father skills making the most beautiful silver

floral ornaments called garlands.

Domenico was active mainly in

Florence where he had, together with his brothers Davide and Benedetto,

a prosperous workshop with many apprentices among them was Michelangelo.

Michelangelo apprenticed to Domenico's workshop in the middle of

1488, but in the following year he transfered to Bertoldo di Giovanni

studio. The reason why Michelangelo, difficult and often arrogant

thirteen years boy, left Domenico's workshop was that Michelangelo

did not appreciate the solid, prosaic and old-fashioned style of his

master. Old-fashioned aspect of Domenico's style was based on two

major things: first he never experimented with oil painting, very modern

and popular among Italian painters of his generation, and second that

his narrative linear compositions inspired on Masaccio's frescos

were merely a reminiscence of Masaccio' innovative works. In his

frescos Masaccio virtuoso captured effect of light and shadow by

applying mathematical perspective, the new feature invented by

Bruneleschi. Bruneleschi's invention of perspective was a milestone

for the development of modern painting.

Although not an

innovator, Ghirlandaio was an excellent craftsman widely celebrated by

Florentines. His brisk observation, solid painting, high degree of

realism and talent for depicting the scenes from the life brought him a

broad publicity.

With the growing prosperity wealthy Florentine citizens of the Florentine Republic, mostly bankers and merchants, began recognize themselves with a self-confidence and self-importance. They became particularly keen on self-portrayal, and was very important for them to be seen. Visual display was an essential component of the public recognition and prestige. The natural path to fulfill a lack of visual display was a commission of frescos or portraits, which the primary function was to glorify and immortalize commissioner himself, his family and friends within traditional framework of religious stories. The goal of the painter was to follow the commissioner's wish to the letter to create a magnificent painting depicting him, his family and friends in the most favorable light with great deal of reality. The abilities to capture elegance and grace of wealthy burghers, their high status, social prestige, moral virtue, heraldic devices and emblems, or magnificence and wealth within the story was highly appreciated and brought the artist prosperity throughout his life. Some of the most important patrons and commissioners were Francesco Sasetti, Giovanni Tornabuoni, and pope Sixtus IV (Francesco della Rovere) among many others .

Ghirlandaio's human and artistic personality

made him the excellent choice to fulfill Florentines' wishes. He was

a painter who could produce a number of conventional frescos depicting

beautiful and powerful religious scene in the center. He filled the free

space of the religious scene with elegant figures of Florentine citizens

dressed in the fashionable costume of his time. They were arranged

rather stiffly in groups of three, or five figures leading by the

commissioner itself, or a person appointed by him. This alludes to a

symbolism of numerical medieval tradition. Three is a heavenly number

that represents tripartite nature of world and heaven, and five

represents a human perfection (a man with outstretched arms and legs

forms a pentagon with the head).

He also painted a number of easel

portraits in which he practiced the style convention imposed by Leon

Battista Alberti in his treatise "On painting" (Della pittura)

from 1435, so admired by Florentine commissioners and patrons.

Generally, frescos, portraits and medals were ordered at the occasion of a birthday, a marriage or death in the patron's family or other special public or business necessities of commissioner. During the Renaissance many of the religious and historical paintings of such painters as Florentines Ghirlandaio (The lives of the Virgin Mary and John the Baptist, 1484) and Benozzo Gozzoli (Procession of the Magi, 1459) and later Venetians Giorgione and Bassano, are considered as genre paintings because of contemporaneous backgrounds and costumes as well as their use of people of the times as models.

In 1485 Giovanni Tornabuoni, a partner in the

Medici bank, commissioned the artist to decorate one of the chapels in

the church of Santa María Novella in Florence with a series of frescos

depicting "The legend of Virgin Mary and John the Baptist".

The frescos depict several sacred scenes taken from the lives of the

Virgin Mary and John the Baptist as if they had taken place in the

palace of a wealthy Florentine burgher.

In these frescos Domenico included the figures of

the leading members of Tornabuoni family represented by Giuliano, Gian

Francesco and Giovanni Battista and their families, friends represented

by Giovanni Tornaquinci and and the contemporary world of Florentine

culture represented by Marsilio Ficino, Cristofero Landino, Demetrius

the Greek, and Angelo Polilziano among others as a spectators of the

sacred event.

Domenico was also commissioned to paint the portrait of Giovanna, the Lorenzo Tornabuoni's wife whom he married on June 15, 1486. Giovanna Tornabuoni was a daughter of the Albizzi family of bankers and politicians, closely related to the Medicis. She gave birth to the son, Giovanni, in October 1487 and died in childbirth in October of 1488.

Before this particular portrait was completed, she was commemorated for ever on the one of the frescos "Visitation" in theTornabuonis chapel in Santa Maria Novella. The centre of the fresco titled "Visitation" depicts the simple but very important biblical scene in which Virgin Mary is visiting Saint Elizabeth, mother of Saint John the Baptist, On the both sides of the fresco two group of young or mature but wealthy Florentine women can be seen. They were engage as viewers in the sacred scene. The psychological interactions between witness of the scene may remain elusive, but the narrative aspect is clear and comprehensive. The remaining background space of the fresco is filled with landscape and cities, animals and plants, classical buildings and reliefs. The pictorial inspiration of the background, without a doubt, was made on Flemish painting "Rolin Madonna" (1436) by van Eyke (now in Louvre, Paris), and "Saint Luke Painting the Virgin" by Rogier van der Weyden (now in Boston Institute of Art, USA). The beautiful, rigid, distinguish woman standing directly underneath the arch of a classical triumphal archway flanked by columns is Giovanna Tornabuoni.

Alike the fresco, the profile portrait of Giovanna brilliantly express her cold serene beauty. The rigid pride of the aristocratic woman in elegant static pose as well as detailed pattern on her magnificent dress with her husband's initial were considered by contemporary jurists as a sign of her husband rank. According to Francesco Barbaro, the public appearance of uper class Florentine's wife, her hair adornments, splendid dress and magnificent jewels, are not questionable signs of her husband wealth and honor ( "On Wifely Dutes" taken from his treatise "De re uxoria", 1416).

The portrait is also emphasizing the fact that

Giovanna is pregnant. It is quite possible that Domenico was able to

draw the cartoon for fresco and later for the portrait before her death.

Giovanna Tornabuoni appears in profile, a characteristic of

the first quarter of the XVth century portraits. This beautiful young

woman, Florentine ideal of woman's beauty, stands out in a clear

contrast of light against dark coming from the niche in the background.

She is dressed in a magnificent garment made of gold brocade with tight,

slitted silk sleeves which highlight her nobility and wealth of her

family. The pattern of her dress is portrayed in great detail,

characteristic for Flemish painting and decorative Italian taste. She is

wearing a valuable piece of jewelry - a gold a pendant or brooch made

of a ruby in a gold setting with three magnificent pearls shining

silky in the soft light. A similar pendent of brooch is laying on the

shelf in the niche behind her. The arrangement of her hair and jewels

that adorn her and the one that is laying in the left ledge of the niche

gives the work a noble grace and elegance. These jewels emphasize her

status as well as her social obligations and necessary physical elegance

as a wife to Lorenzo Tornabuoni.

in the niche behind her there are

some objects, a half open Book of hours, recently used, and a

rosary, which have a strictly symbolic value. These objects depict the

beauty of her mind, promote her pious ideal as a wife and mother,

amplify her modesty, virtue and devotion.

In the niche, between the prayer book and red coral rosary beads there is also a little

note alluding to the beautiful soul of the portrayed woman. An epigram

written in Latin by the Roman poet Martial , "ARS UTINAM MORES

ANIMUN QUE EFFINGERE POSSES PULCHRIOR IN TERRIS NULLA TABELLA FORET

MCCCCLXXXVIII." (Art, if only you could portray character and moral

spirit, there would be no more beautiful picture on earth, 1488).

Derived from Early Renaissance pictorial conventions Dominico's portrait depicts Giovanna as a beautiful, educated, solemn, pious, obedient, dependent on men, woman, wife and mother of upper class Florentine. Thematically, stylistically and compositionally intended to be a conformation of grace, elegance, social status of the sitter, it is rather a XVth century advertisement of her family honor and prestige. Giovanna's individualism and personal traits have been omitted. In contrast to the melancholic and sensual portrait of Ginevra de Benci painted in 1474 by Leonardo da Vinci, Giovanna's profiled face and body pose present an absolute lack of female sensitivity and sexuality.